While most companies compete for Bay Area "AI engineers" at $500K, we've tripled revenue with zero layoffs over the past four years.

Our approach is straightforward: focus on team structure that delivers results rather than following market trends.

Our system: 1 ML engineer for every full-stack engineer. All full-stacks have solid Python skills to handle ML bottlenecks. The ML engineer owns model architecture, training optimization, and hyperparameter tuning. Full-stacks handle data pipelines, API scaling, production monitoring, and performance optimization.

This 1:1 ratio consistently outperforms teams with 5-10 "AI engineers."

The numbers: 95%+ retention. Zero layoffs. Revenue 3x. 12-month voluntary attrition: <5%. Average tenure: 3.1 years.

How we avoided the $500K hiring war: Our engineers are in Ukraine and Europe. Boston-based company, 100% remote since before the COVID-19 pandemic. Engineers outside Silicon Valley often bring stronger fundamentals. Bay Area market dynamics don't influence their career decisions. They focus on solving problems rather than optimizing for title progression.

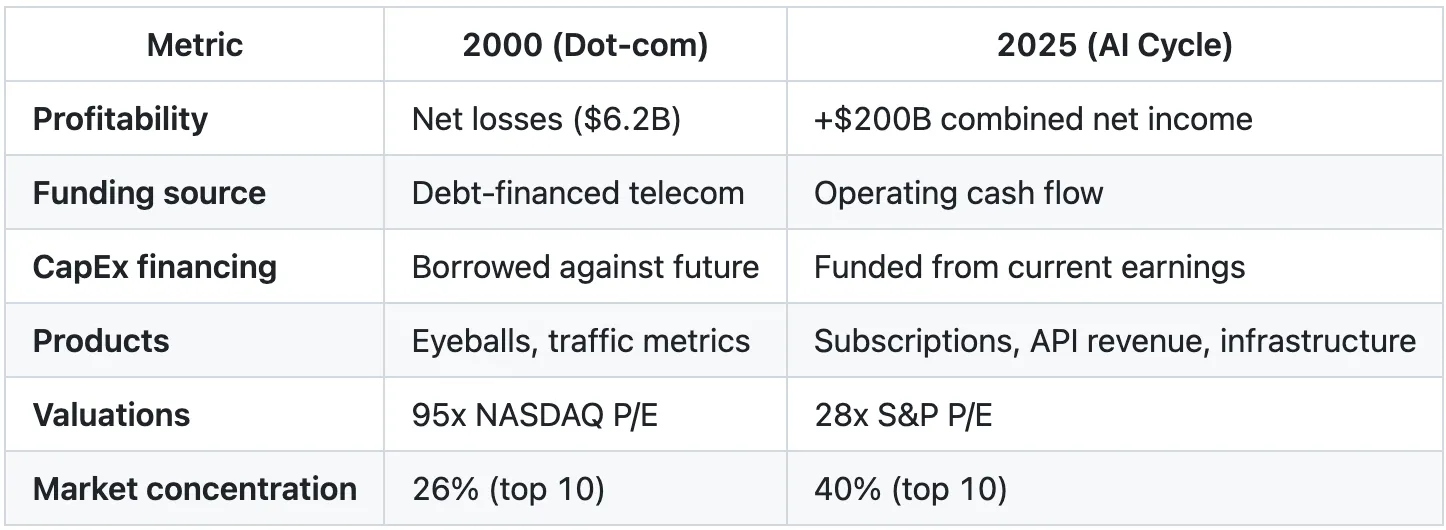

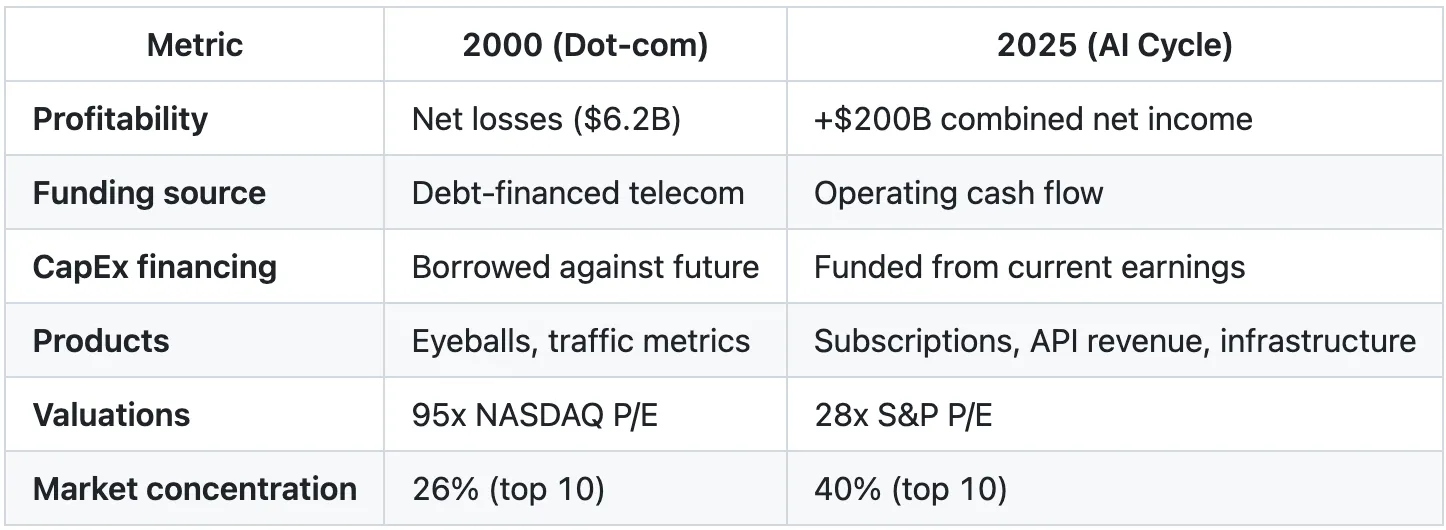

The current conversation around AI focuses on job displacement and market volatility. What matters more is understanding what's actually happening and why this transformation differs fundamentally from 2000.

NVIDIA has become the first company to surpass a market capitalization of $5 trillion. That's larger than Germany's entire GDP. One chipmaker is now worth more than the world's fourth-largest economy.

The concentration is unprecedented, and comparisons to previous bubbles are inevitable. But there's a fundamental difference: these companies generate substantial revenue.

NVIDIA reported $130.5B in FY2025 revenue and record profitability. Datacenter demand is sold out for quarters ahead. OpenAI is projected to reach $13-20 billion in annualized revenue by late 2025, with 800 million weekly active users. Microsoft's AI business surpassed $75 billion annually in Azure cloud revenue (up 34% YoY).

Compare that to 2000. The 199 internet stocks tracked by Morgan Stanley collectively lost $6.2 billion on $21 billion in sales. 74% reported negative cash flows. The valuations had no foundation in operational performance.

Pets.com in 1999? $619,000 in revenue and $147 million in losses. The business model relied on selling products below cost to capture market share.

OpenAI in 2025? $13-20B ARR from 5 million paying business customers. $20/month consumer subscriptions. $30/user/month enterprise deals. Billions in API usage fees.

The dot-com era funded business models that couldn't sustain themselves. Today's infrastructure spending comes from companies with proven revenue streams.

Even Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell said it explicitly: "These companies actually have earnings. They actually have business models and profits and that kind of thing. So it's really a different thing."

The profitability of these companies drives massive investment in AI talent, which leads to an uncomfortable truth about what they're actually buying.

AI engineers earn a median salary of $245,000, compared to $187,200 for software engineers, a 31% premium. At OpenAI, it's $910,000, while at Meta, it's $560,000. When 73% can't explain how transformers work, that premium reflects market dynamics rather than actual expertise.

Watch the shift by level: entry-level premiums dropped from 10.7% to 6.2%, while staff+ rose from 15.8% to 18.7%. The premium is concentrated at senior levels. Entry-level AI engineers are becoming commoditized, just like full-stack engineers were before the COVID-19 pandemic.

The market will correct. It always does.

We built our system deliberately around this reality. ML engineers excel at building models, training, and optimization. However, they struggle with fundamental engineering and architectural problems. Scaling APIs. Debugging production issues. Building resilient pipelines.

The first ML hire was great at the ML work. But every infrastructure problem became a bottleneck. Features sat waiting for architectural decisions. Production issues took days to debug.

That's when we formalized the approach: pairing each ML engineer with full-stack engineers who have expertise in Python. The ML engineer owns the model work. Full stacks handle the engineering fundamentals. (Learn more about how we approach machine learning projects.)

On every project, we have a lead engineer who acts as the architect. They make the structural decisions. The ML engineer focuses on what they're actually good at. Full stacks execute on solid architecture.

This isn't about replacing ML engineers. It's about letting them focus on the 20% that requires deep ML expertise instead of struggling with the 80% that's basic engineering.

The salary premium is a surface-level indicator. The more significant trend is where capital is being deployed at scale.

The four major cloud providers are spending $315-364 billion in 2025 alone. Every dollar is funded from the operating cash flow of profitable operations.

This is the structural difference from 2000. Telecom companies deployed $500 billion in debt-financed infrastructure in the late 1990s. 85-95% of the capacity became "dark fiber" that remained unused. The companies collapsed under the debt they couldn't service.

Today's spending is backed by companies like Microsoft, which generated $101.8 billion in net income in fiscal 2025. They're spending from earnings, not borrowing against future promises.

I covered this in detail in Big Tech's $364 Billion Bet on an Uncertain Future. Key takeaway: this is real infrastructure backed by real profits.

This infrastructure spending connects directly to employment patterns that are reshaping the industry.

Between 80,000 and 132,000 tech employees lost their jobs in 2025 through November. But here's the pattern most people miss: AI eliminates jobs at certain skill levels while amplifying expertise at others.

Salesforce cut 4,000 customer support roles (9,000 to 5,000). CEO Marc Benioff: "I need fewer heads." Result: 17% cost reduction, AI agents handling 1M+ conversations.

Klarna reduced workforce 40%. An AI assistant is performing the work of 700 customer service employees. Query resolution: 11 minutes to 2 minutes. Revenue per employee: $400K to $700K annually.

IBM cut hundreds of HR jobs, replaced by the "AskHR" AI chatbot. Handles 94% of routine HR tasks.

Skills becoming obsolete include manual data entry, basic coding without deep understanding, routine customer queries, simple content writing, basic graphic design, and repetitive administrative tasks.

Roles focused primarily on execution with minimal judgment face the highest displacement risk.

Our 1:1 ratio works because we're amplifying engineers, not replacing them. When AI automates routine tasks, engineers who can handle complex problems become more valuable, not less.

The data on productivity reveals a more complex picture than most assume.

Companies are paying 31% premiums for "AI engineers." The data shows individual developers reporting 20% faster completion times with AI tools, while measured organizational productivity drops 19%.

I covered this in detail in The State of AI in Engineering: Q3 2025. The pattern is consistent across multiple studies: individual speed increases, while organizational throughput remains flat or declines. The code is "getting bigger and buggier." Junior defect rates are 4x higher. Seniors spend their productivity gains verifying AI output instead of shipping features.

The economic implication? Companies are paying bubble premiums for a productivity gain that doesn't materialize at the organization level. They're betting $500K salaries will solve scaling problems when the actual bottleneck is architectural oversight and code review. AI amplifies expertise; it doesn't replace it.

The real productivity gains come from redesigning workflows around AI capabilities, not just adding AI tools to existing processes.

This creates a structural problem: if companies only want seniors who can supervise AI, where do those seniors come from?

New grad hiring is down 25% from 2023 to 2024. Entry-level software engineering jobs are being eliminated faster than any other category.

Companies only want seniors who can supervise AI. However, you can't hire a senior engineer who was never a junior engineer.

In five years, we'll face a shortage of experienced engineers because we stopped training juniors today.

This represents a quiet systemic risk. Companies optimize for the next quarter without considering who will build the next generation of engineering leaders.

As I wrote in AI Won't Save Us From the Talent Crisis We Created, the industry's obsession with senior-only hiring has created a pipeline problem that will only worsen.

Companies that invest in developing talent, not just buying it, will have the advantage when the correction comes.

The pipeline problem exists primarily in Big Tech. The startup ecosystem shows different characteristics—classic bubble indicators.

Big Tech prints money. Record profits back their infrastructure spending. But the startup ecosystem? That's where the bubble math stops working.

Venture capital to AI in 2025:

By various estimates, ~500 AI "unicorns" emerged in 2025, valued at over $1 billion. Most have no profits.

Valuations that don't make sense:

The math gets absurd. By various estimates, $560 billion has been invested in AI infrastructure (2023-2025) while AI-specific revenue reaches ~$35 billion. That's a 16:1 investment-to-revenue ratio. Infrastructure spend has outpaced monetization by an order of magnitude.

The project failure rates are significant:

Yet Microsoft Copilot customers report a 68% boost in job satisfaction alongside productivity gains.

The difference? Implementation sophistication, not just adoption.

Companies that succeed:

If you're exploring generative AI implementation, these patterns should guide your approach.

The comparison to 2000 is instructive but incomplete. The crash mechanics will differ.

The dot-com crash didn't kill the internet. It killed companies that confused narrative for value. This AI transformation won't crash the same way.

Here's the structural difference:

But legitimate risks remain:

The critical question isn't whether AI will transform the economy—the transformation is already underway. The question is whether current startup valuations and infrastructure investments can be justified by the near-term returns they generate.

Goldman Sachs argues that the spending is justified, estimating a potential value of $8-19 trillion to the US economy. AI investment remains below 1% of GDP, compared to 2-5% in prior technology cycles.

Both things are true:

Unlike 2000, even if corrections occur, the infrastructure is built by companies that can absorb losses while maintaining profitability in core businesses. The technology works. The profitable companies keep operating. The real transformation continues.

Geographic arbitrage becomes more relevant in this context.

The Bay Area talent war has created an artificial scarcity problem. When everyone competes for the same 50,000 engineers within a 50-mile radius, salaries become disconnected from the value delivered. $500K for junior "AI engineers" who can't debug Python? That's not a market, that's a bubble.

The alternative isn't cheaper engineers. It's better talent pools.

We've been 100% remote since before the COVID-19 pandemic. Our engineers are based in Ukraine, Poland, Romania, and increasingly, talented US engineers outside the Bay Area who'd rather work remotely than relocate for inflated compensation tied to inflated cost of living.

Remote-first changes the math:

This isn't about replacing anyone. It's about escaping artificial constraints. When you compete for talent in the same 50-mile radius as everyone else, you're bidding against bubble prices for access to the same talent pool.

When the market corrects (and specific segments will), companies built on $500,000 salary structures will scramble. Companies that develop sustainable teams with global talent pools will continue to succeed.

Remote-first since before COVID means we had a four-year head start on distributed team operations. That advantage compounds during a crisis, whether it's a pandemic, a market correction, or a talent shortage.

For engineering leaders, the path forward requires specific strategic choices.

The data points to several approaches that consistently deliver results:

Can they debug a memory leak? Build a distributed system? Do they know Python well enough to fix ML bottlenecks?

Actual engineering skills matter more than AI certificates.

When the premium collapses (and it will), you want engineers who can still ship.

One ML engineer paired with a Python-fluent full-stack consistently outperforms ten "AI engineers."

The ML engineer owns the 20% that requires deep expertise. Full stacks handle the 80% that's engineering fundamentals.

The Bay Area hiring war is an artificial scarcity problem. When everyone competes in the same 50-mile radius, you're bidding against bubble prices for the same talent pool.

Build remote-first. Look at talented engineers in Ukraine, Poland, Romania, US cities outside SF, anywhere with a strong engineering culture but without Bay Area salary inflation. You'll find engineers who prioritize building great products over optimizing their next job hop.

The constraint isn't talent availability. It's geographic self-limitation.

When everyone else pays $500K for junior AI engineers, you're building sustainable teams. When the correction comes, you're still operating.

AI is effective when integrated into existing workflows by individuals who understand both the domain and the technology.

It fails when treated as a magic replacement for expertise.

Most companies bolt AI onto existing processes. You need to rethink how work gets done fundamentally. That's where the 90% success rate comes from.

Someone has to train the next generation of seniors. If everyone only hires experienced engineers, where do those engineers come from?

The companies that develop talent, not just buy it, will dominate when the correction comes.

AI is a powerful tool that amplifies expertise when used by capable hands.

Companies that treat it as a replacement for thinking will struggle. Companies that use it to multiply the effectiveness of experienced professionals will have an advantage.

Yes, this is a bubble. But it differs fundamentally from 2000. The infrastructure is real, backed by operating profits, not debt. The revenue exists. The products work. When corrections happen, the technology doesn't disappear—unprofitable companies do.

This is an industrial bubble where infrastructure is being built faster than monetization can scale. Startup valuations exceed any reasonable near-term revenue projections. 95% of pilots fail, yet billions continue flowing.

The difference from 2000? When this corrects, the infrastructure remains. The technology works. The profitable companies keep operating. The transformation continues.

Good engineers will remain in demand. The ones who can build, debug, and ship. The ones who solve problems rather than chase titles.

Most companies optimize for short-term market dynamics rather than long-term systems. They're buying "AI engineers" at significant premiums instead of building teams that can deliver consistently.

When the correction comes, the companies still operating will be the ones that built for sustainability.

The question for your organization: are you creating something that survives the correction?

At NineTwoThree, we've spent over a decade building AI and ML solutions that generate measurable returns. Our team of Ph.D.-level engineers and product managers has delivered 150+ projects for companies like Consumer Reports, FanDuel, and SimpliSafe.

We don't just build AI—we help you deploy solutions that deliver positive ROI within weeks, not months.

Schedule a discovery call with our founders to discuss your AI strategy, or explore our AI consulting services to learn how we can help you navigate this transformation.

While most companies compete for Bay Area "AI engineers" at $500K, we've tripled revenue with zero layoffs over the past four years.

Our approach is straightforward: focus on team structure that delivers results rather than following market trends.

Our system: 1 ML engineer for every full-stack engineer. All full-stacks have solid Python skills to handle ML bottlenecks. The ML engineer owns model architecture, training optimization, and hyperparameter tuning. Full-stacks handle data pipelines, API scaling, production monitoring, and performance optimization.

This 1:1 ratio consistently outperforms teams with 5-10 "AI engineers."

The numbers: 95%+ retention. Zero layoffs. Revenue 3x. 12-month voluntary attrition: <5%. Average tenure: 3.1 years.

How we avoided the $500K hiring war: Our engineers are in Ukraine and Europe. Boston-based company, 100% remote since before the COVID-19 pandemic. Engineers outside Silicon Valley often bring stronger fundamentals. Bay Area market dynamics don't influence their career decisions. They focus on solving problems rather than optimizing for title progression.

The current conversation around AI focuses on job displacement and market volatility. What matters more is understanding what's actually happening and why this transformation differs fundamentally from 2000.

NVIDIA has become the first company to surpass a market capitalization of $5 trillion. That's larger than Germany's entire GDP. One chipmaker is now worth more than the world's fourth-largest economy.

The concentration is unprecedented, and comparisons to previous bubbles are inevitable. But there's a fundamental difference: these companies generate substantial revenue.

NVIDIA reported $130.5B in FY2025 revenue and record profitability. Datacenter demand is sold out for quarters ahead. OpenAI is projected to reach $13-20 billion in annualized revenue by late 2025, with 800 million weekly active users. Microsoft's AI business surpassed $75 billion annually in Azure cloud revenue (up 34% YoY).

Compare that to 2000. The 199 internet stocks tracked by Morgan Stanley collectively lost $6.2 billion on $21 billion in sales. 74% reported negative cash flows. The valuations had no foundation in operational performance.

Pets.com in 1999? $619,000 in revenue and $147 million in losses. The business model relied on selling products below cost to capture market share.

OpenAI in 2025? $13-20B ARR from 5 million paying business customers. $20/month consumer subscriptions. $30/user/month enterprise deals. Billions in API usage fees.

The dot-com era funded business models that couldn't sustain themselves. Today's infrastructure spending comes from companies with proven revenue streams.

Even Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell said it explicitly: "These companies actually have earnings. They actually have business models and profits and that kind of thing. So it's really a different thing."

The profitability of these companies drives massive investment in AI talent, which leads to an uncomfortable truth about what they're actually buying.

AI engineers earn a median salary of $245,000, compared to $187,200 for software engineers, a 31% premium. At OpenAI, it's $910,000, while at Meta, it's $560,000. When 73% can't explain how transformers work, that premium reflects market dynamics rather than actual expertise.

Watch the shift by level: entry-level premiums dropped from 10.7% to 6.2%, while staff+ rose from 15.8% to 18.7%. The premium is concentrated at senior levels. Entry-level AI engineers are becoming commoditized, just like full-stack engineers were before the COVID-19 pandemic.

The market will correct. It always does.

We built our system deliberately around this reality. ML engineers excel at building models, training, and optimization. However, they struggle with fundamental engineering and architectural problems. Scaling APIs. Debugging production issues. Building resilient pipelines.

The first ML hire was great at the ML work. But every infrastructure problem became a bottleneck. Features sat waiting for architectural decisions. Production issues took days to debug.

That's when we formalized the approach: pairing each ML engineer with full-stack engineers who have expertise in Python. The ML engineer owns the model work. Full stacks handle the engineering fundamentals. (Learn more about how we approach machine learning projects.)

On every project, we have a lead engineer who acts as the architect. They make the structural decisions. The ML engineer focuses on what they're actually good at. Full stacks execute on solid architecture.

This isn't about replacing ML engineers. It's about letting them focus on the 20% that requires deep ML expertise instead of struggling with the 80% that's basic engineering.

The salary premium is a surface-level indicator. The more significant trend is where capital is being deployed at scale.

The four major cloud providers are spending $315-364 billion in 2025 alone. Every dollar is funded from the operating cash flow of profitable operations.

This is the structural difference from 2000. Telecom companies deployed $500 billion in debt-financed infrastructure in the late 1990s. 85-95% of the capacity became "dark fiber" that remained unused. The companies collapsed under the debt they couldn't service.

Today's spending is backed by companies like Microsoft, which generated $101.8 billion in net income in fiscal 2025. They're spending from earnings, not borrowing against future promises.

I covered this in detail in Big Tech's $364 Billion Bet on an Uncertain Future. Key takeaway: this is real infrastructure backed by real profits.

This infrastructure spending connects directly to employment patterns that are reshaping the industry.

Between 80,000 and 132,000 tech employees lost their jobs in 2025 through November. But here's the pattern most people miss: AI eliminates jobs at certain skill levels while amplifying expertise at others.

Salesforce cut 4,000 customer support roles (9,000 to 5,000). CEO Marc Benioff: "I need fewer heads." Result: 17% cost reduction, AI agents handling 1M+ conversations.

Klarna reduced workforce 40%. An AI assistant is performing the work of 700 customer service employees. Query resolution: 11 minutes to 2 minutes. Revenue per employee: $400K to $700K annually.

IBM cut hundreds of HR jobs, replaced by the "AskHR" AI chatbot. Handles 94% of routine HR tasks.

Skills becoming obsolete include manual data entry, basic coding without deep understanding, routine customer queries, simple content writing, basic graphic design, and repetitive administrative tasks.

Roles focused primarily on execution with minimal judgment face the highest displacement risk.

Our 1:1 ratio works because we're amplifying engineers, not replacing them. When AI automates routine tasks, engineers who can handle complex problems become more valuable, not less.

The data on productivity reveals a more complex picture than most assume.

Companies are paying 31% premiums for "AI engineers." The data shows individual developers reporting 20% faster completion times with AI tools, while measured organizational productivity drops 19%.

I covered this in detail in The State of AI in Engineering: Q3 2025. The pattern is consistent across multiple studies: individual speed increases, while organizational throughput remains flat or declines. The code is "getting bigger and buggier." Junior defect rates are 4x higher. Seniors spend their productivity gains verifying AI output instead of shipping features.

The economic implication? Companies are paying bubble premiums for a productivity gain that doesn't materialize at the organization level. They're betting $500K salaries will solve scaling problems when the actual bottleneck is architectural oversight and code review. AI amplifies expertise; it doesn't replace it.

The real productivity gains come from redesigning workflows around AI capabilities, not just adding AI tools to existing processes.

This creates a structural problem: if companies only want seniors who can supervise AI, where do those seniors come from?

New grad hiring is down 25% from 2023 to 2024. Entry-level software engineering jobs are being eliminated faster than any other category.

Companies only want seniors who can supervise AI. However, you can't hire a senior engineer who was never a junior engineer.

In five years, we'll face a shortage of experienced engineers because we stopped training juniors today.

This represents a quiet systemic risk. Companies optimize for the next quarter without considering who will build the next generation of engineering leaders.

As I wrote in AI Won't Save Us From the Talent Crisis We Created, the industry's obsession with senior-only hiring has created a pipeline problem that will only worsen.

Companies that invest in developing talent, not just buying it, will have the advantage when the correction comes.

The pipeline problem exists primarily in Big Tech. The startup ecosystem shows different characteristics—classic bubble indicators.

Big Tech prints money. Record profits back their infrastructure spending. But the startup ecosystem? That's where the bubble math stops working.

Venture capital to AI in 2025:

By various estimates, ~500 AI "unicorns" emerged in 2025, valued at over $1 billion. Most have no profits.

Valuations that don't make sense:

The math gets absurd. By various estimates, $560 billion has been invested in AI infrastructure (2023-2025) while AI-specific revenue reaches ~$35 billion. That's a 16:1 investment-to-revenue ratio. Infrastructure spend has outpaced monetization by an order of magnitude.

The project failure rates are significant:

Yet Microsoft Copilot customers report a 68% boost in job satisfaction alongside productivity gains.

The difference? Implementation sophistication, not just adoption.

Companies that succeed:

If you're exploring generative AI implementation, these patterns should guide your approach.

The comparison to 2000 is instructive but incomplete. The crash mechanics will differ.

The dot-com crash didn't kill the internet. It killed companies that confused narrative for value. This AI transformation won't crash the same way.

Here's the structural difference:

But legitimate risks remain:

The critical question isn't whether AI will transform the economy—the transformation is already underway. The question is whether current startup valuations and infrastructure investments can be justified by the near-term returns they generate.

Goldman Sachs argues that the spending is justified, estimating a potential value of $8-19 trillion to the US economy. AI investment remains below 1% of GDP, compared to 2-5% in prior technology cycles.

Both things are true:

Unlike 2000, even if corrections occur, the infrastructure is built by companies that can absorb losses while maintaining profitability in core businesses. The technology works. The profitable companies keep operating. The real transformation continues.

Geographic arbitrage becomes more relevant in this context.

The Bay Area talent war has created an artificial scarcity problem. When everyone competes for the same 50,000 engineers within a 50-mile radius, salaries become disconnected from the value delivered. $500K for junior "AI engineers" who can't debug Python? That's not a market, that's a bubble.

The alternative isn't cheaper engineers. It's better talent pools.

We've been 100% remote since before the COVID-19 pandemic. Our engineers are based in Ukraine, Poland, Romania, and increasingly, talented US engineers outside the Bay Area who'd rather work remotely than relocate for inflated compensation tied to inflated cost of living.

Remote-first changes the math:

This isn't about replacing anyone. It's about escaping artificial constraints. When you compete for talent in the same 50-mile radius as everyone else, you're bidding against bubble prices for access to the same talent pool.

When the market corrects (and specific segments will), companies built on $500,000 salary structures will scramble. Companies that develop sustainable teams with global talent pools will continue to succeed.

Remote-first since before COVID means we had a four-year head start on distributed team operations. That advantage compounds during a crisis, whether it's a pandemic, a market correction, or a talent shortage.

For engineering leaders, the path forward requires specific strategic choices.

The data points to several approaches that consistently deliver results:

Can they debug a memory leak? Build a distributed system? Do they know Python well enough to fix ML bottlenecks?

Actual engineering skills matter more than AI certificates.

When the premium collapses (and it will), you want engineers who can still ship.

One ML engineer paired with a Python-fluent full-stack consistently outperforms ten "AI engineers."

The ML engineer owns the 20% that requires deep expertise. Full stacks handle the 80% that's engineering fundamentals.

The Bay Area hiring war is an artificial scarcity problem. When everyone competes in the same 50-mile radius, you're bidding against bubble prices for the same talent pool.

Build remote-first. Look at talented engineers in Ukraine, Poland, Romania, US cities outside SF, anywhere with a strong engineering culture but without Bay Area salary inflation. You'll find engineers who prioritize building great products over optimizing their next job hop.

The constraint isn't talent availability. It's geographic self-limitation.

When everyone else pays $500K for junior AI engineers, you're building sustainable teams. When the correction comes, you're still operating.

AI is effective when integrated into existing workflows by individuals who understand both the domain and the technology.

It fails when treated as a magic replacement for expertise.

Most companies bolt AI onto existing processes. You need to rethink how work gets done fundamentally. That's where the 90% success rate comes from.

Someone has to train the next generation of seniors. If everyone only hires experienced engineers, where do those engineers come from?

The companies that develop talent, not just buy it, will dominate when the correction comes.

AI is a powerful tool that amplifies expertise when used by capable hands.

Companies that treat it as a replacement for thinking will struggle. Companies that use it to multiply the effectiveness of experienced professionals will have an advantage.

Yes, this is a bubble. But it differs fundamentally from 2000. The infrastructure is real, backed by operating profits, not debt. The revenue exists. The products work. When corrections happen, the technology doesn't disappear—unprofitable companies do.

This is an industrial bubble where infrastructure is being built faster than monetization can scale. Startup valuations exceed any reasonable near-term revenue projections. 95% of pilots fail, yet billions continue flowing.

The difference from 2000? When this corrects, the infrastructure remains. The technology works. The profitable companies keep operating. The transformation continues.

Good engineers will remain in demand. The ones who can build, debug, and ship. The ones who solve problems rather than chase titles.

Most companies optimize for short-term market dynamics rather than long-term systems. They're buying "AI engineers" at significant premiums instead of building teams that can deliver consistently.

When the correction comes, the companies still operating will be the ones that built for sustainability.

The question for your organization: are you creating something that survives the correction?

At NineTwoThree, we've spent over a decade building AI and ML solutions that generate measurable returns. Our team of Ph.D.-level engineers and product managers has delivered 150+ projects for companies like Consumer Reports, FanDuel, and SimpliSafe.

We don't just build AI—we help you deploy solutions that deliver positive ROI within weeks, not months.

Schedule a discovery call with our founders to discuss your AI strategy, or explore our AI consulting services to learn how we can help you navigate this transformation.